Deakin's Great White Gamble

- DateSat, 20 Aug 2016

On 20 August 1908, a fleet of United States Navy vessels known as the ‘Great White Fleet’ arrived in Sydney.

The fleet was so called because the hulls of the 16 U.S. battleships and their escorts were a stark white colour, to make them stand out and distinguish them from other warships.

The fleet was a pure propaganda exercise. U.S. President, Theodore Roosevelt, ordered the fleet to circumnavigate the globe as a way of demonstrating America’s new naval power. Before the U.S. began building up its naval capacity in the late nineteenth century, the Royal Navy of Great Britain reigned supreme over the seas. It was the superiority of the Royal Navy that led some to assume it would look after the defence of Australia as well. A small squadron of British ships was based in Sydney, but many considered that presence totally inadequate.

In the early days of Federation, most Australians considered themselves Britons. When Australia became a nation, it was tied very much to Britain in terms of foreign policy and defence. In these early years, it was somewhat radical to think of the Australian government setting its own direction for foreign policy and not toeing the Westminster line.

Australia’s prime minister, Alfred Deakin, took a different view. While certainly seeing Australia as a British nation, he also recognised the need for the Australian government to see to the defence of its own territory, and to exercise foreign policy separately from London. To that end, Deakin extended an invitation to Roosevelt, inviting the Great White Fleet to visit Sydney.

No British battleship, or a fleet remotely this size, had ever entered Australian waters before.

In extending the invitation to Roosevelt, Deakin expressed his view that 'no other Federation in the world possesses so many features [in common with] the United States as does the Commonwealth of Australia'.

Rather than trying to assert independence per se, or look to America for defence, Deakin was merely trying to make the point that the British government was overlooking its antipodean dominion.

The British Colonial Office, which had to transmit the request, urged the fleet, and the White House, not to accept it, but ultimately Roosevelt agreed. The British must have been fuming, but the deed was done.

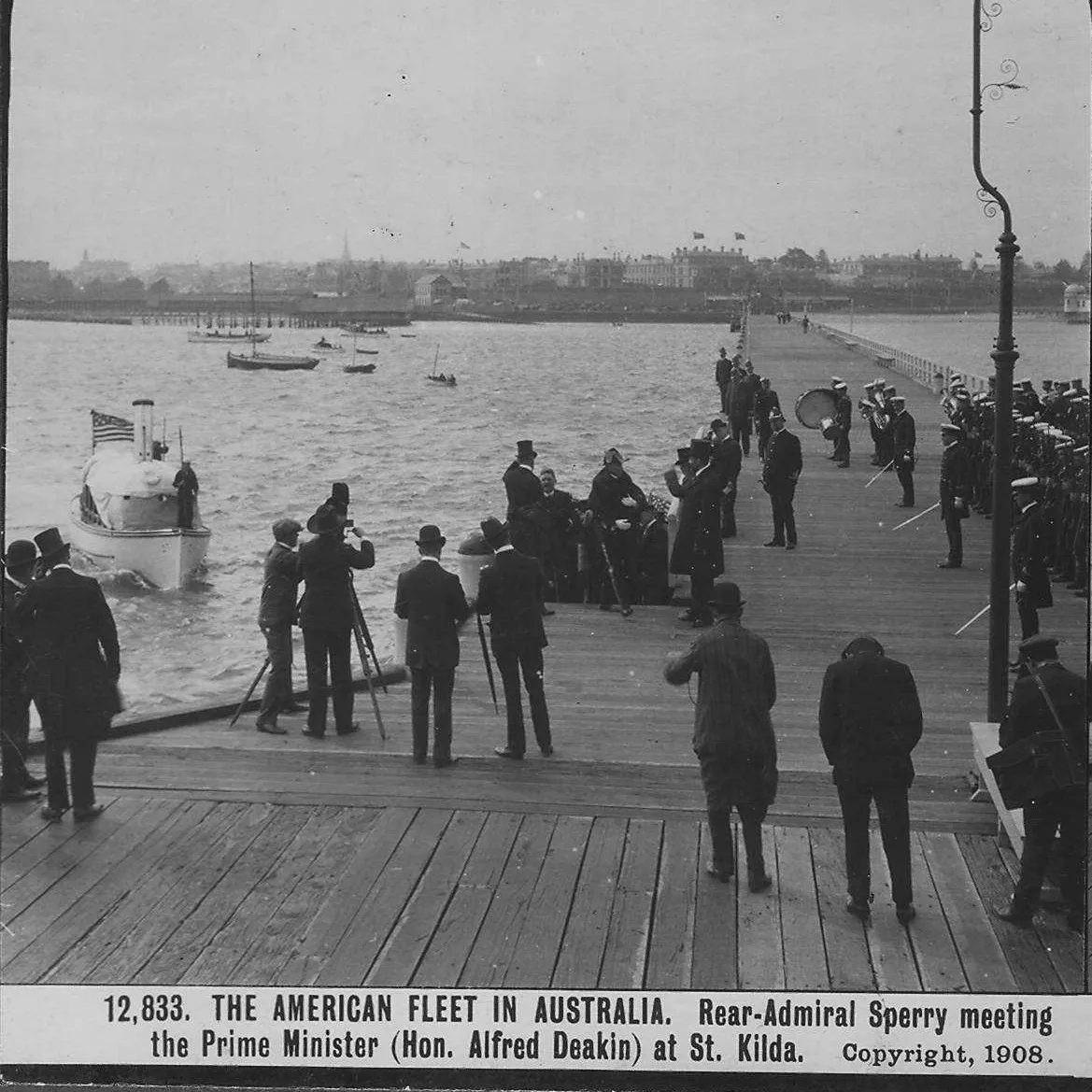

The fleet arrived in Sydney on 20 August to great ceremony. Most Australians had never seen ships like these before, and vast crowds turned out to see the splendid vessels in all their glory. But it wasn’t just for the punters; Deakin had a real point to make about Australia’s defence, and its place among the community of nations.

Deakin had long advocated for an Australian navy, and those plans faced staunch opposition both at home and abroad. The Great White Fleet’s visit changed that. It gave Deakin the capital he needed to press for, and ultimately achieve, an Australian naval force.

Deakin said 'for the British Navy there would be no Australia. That does not mean that Australia should sit under the shelter of the British Navy – those who say we should sit still are not worthy of the name Briton. We can add to the Squadron in these seas from our own blood and intelligence something that will launch us on the beginning of a naval career, and may in time create a force which shall rank amongst the defences of the Empire.'

The visit was a great success and certainly helped the cause of a new Australian Navy, which became a reality in 1911.

The visit also demonstrated one of the key principles of Australian nationhood; it is the elected Australian government that makes Australian foreign and defence policy. Controversial at the time, more than a century later this has become established fact. This wasn’t entirely due to Deakin’s efforts, but his decision to approach Roosevelt, bypass London, and take a stand for Australian independence clearly had a significant impact on future events.