1988: Rights and freedoms

You have the right

Date

3 September 1988

Question

A Proposed Law: To alter the Constitution to extend the right to trial by jury, to extend freedom of religion, and to ensure fair terms for persons whose property is acquired by any government.

Do you approve this proposed alteration?

Result

A large majority of Australians in all states voted NO. The Constitution was not changed.

NSW

Yes: 965,045 (29.65%), No: 2,289,645 (70.35%)

VIC

Yes: 816,057 (33.42%), No: 1,625,484 (66.58%)

QLD

Yes: 506,710 (32.9%), No: 1,033,645 (67.10%)

WA

Yes: 233,917 (28.14%), No: 597,322 (71.86%)

SA

Yes: 223,038 (26.01%), No: 634,438 (73.99%)

TAS

Yes: 70,987 (25.49%), No: 207,486 (74.51%)

ACT

Yes: 60,064 (40.71%), No: 87,460 (59.29%)

NT

Yes: 20,503 (37.14%), No: 34,699 (62.86%)

Total

Yes: 2,892,828 (30.79%), No: 6,503,752 (69.21%)

In 1988, Australians were asked to add some of those rights to the Constitution. On paper, it sounded uncontroversial, but there was a lot of debate about the specifics. Some saw an overdue change that would end some state laws they felt were unfair or discriminatory, while others saw a cynical power grab.

Only a handful of individual rights were mentioned in the Constitution as written in 1901, most notably the right to a jury trial and freedom of religion. Many of the other rights we take for granted, like freedom of speech, weren't explicitly spelled out and instead implied by courts.

The Bicentennial in 1988, 200 years after the First Fleet landed in Sydney Harbour, seemed to the Hawke government a good opportunity to commit to spelling out those rights in the Constitution. The proposal strengthened the existing protections relating to trial by jury, freedom of religion and protection against compulsory acquisition of property. The intent was to ensure state governments would also be required to uphold those rights.

Constitutional experts and lawyers had endorsed the changes, and civil liberties groups were supportive. But some state governments saw the change as an attack against their policies and their autonomy. One concern was whether the religious freedom clause would threaten funding for religious schools, an argument advanced by independent and religious educational organisations.

The rights amendment was one of four put to voters, the others being about fair elections, local government and the length of parliamentary terms. More than two-thirds of voters said no. The other proposals were rejected by similar margins. Subsequent High Court rulings recognised 'implied' rights in the Constitution, most notably the right to 'freedom of political communication'. To this day, constitutional scholars, political leaders and the Australian public continue to debate whether our fundamental rights should be protected, and by whom.

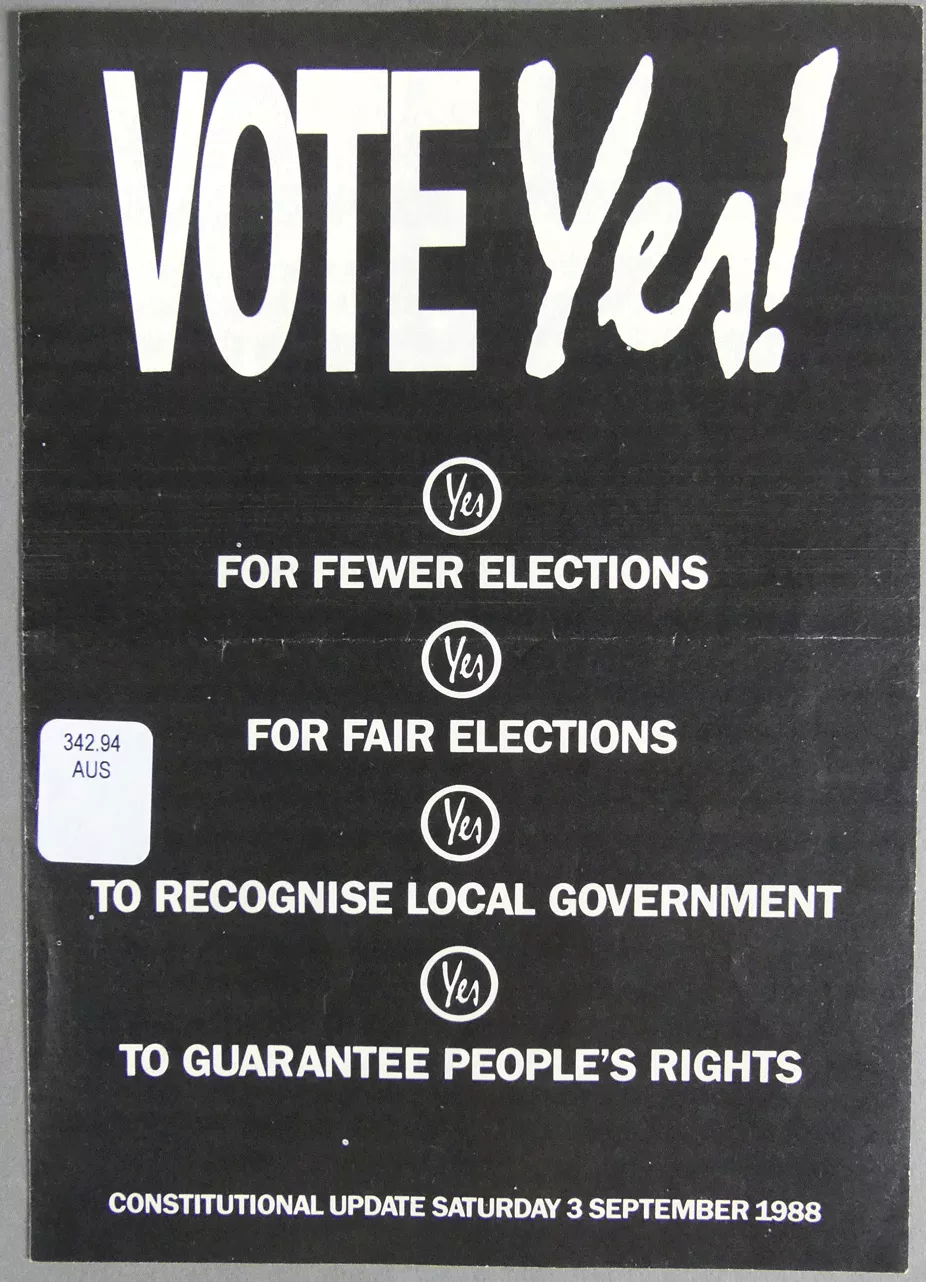

Booklet presenting the case for change, promoted by the Hawke government and marketed as an 'update' to the Constitution, 1988.

Museum of Australian Democracy Collection 2017-1136

Extract from the official YES case

'Voting YES will guarantee all Australians three basic rights against the actions of all Governments: trial by jury for people facing serious criminal charges, fair compensation if a government takes your property [and] freedom of religion. State and Territory Governments are not bound to observe these rights.

In the past, State Governments have confiscated privately owned property without providing just terms. The proposal means that whenever any government takes your property you will receive fair compensation.

There is no common law protection of the right to religious freedom. Nor are the States or Territories obliged to observe this right. This proposal will apply the guarantee of religious freedom consistently throughout Australia.

The proposal does not prevent Government aid to religious schools or hospitals.

The proposal does not mean prayers will be prohibited in Government schools or at public ceremonies.

[The changes] do not seek any extra powers for politicians or governments. They offer extra rights and guarantees for the people.

At last there is a chance to change the Constitution for the benefit of people and not politicians.'

Source: Official referendum handbook, MoAD item 12445

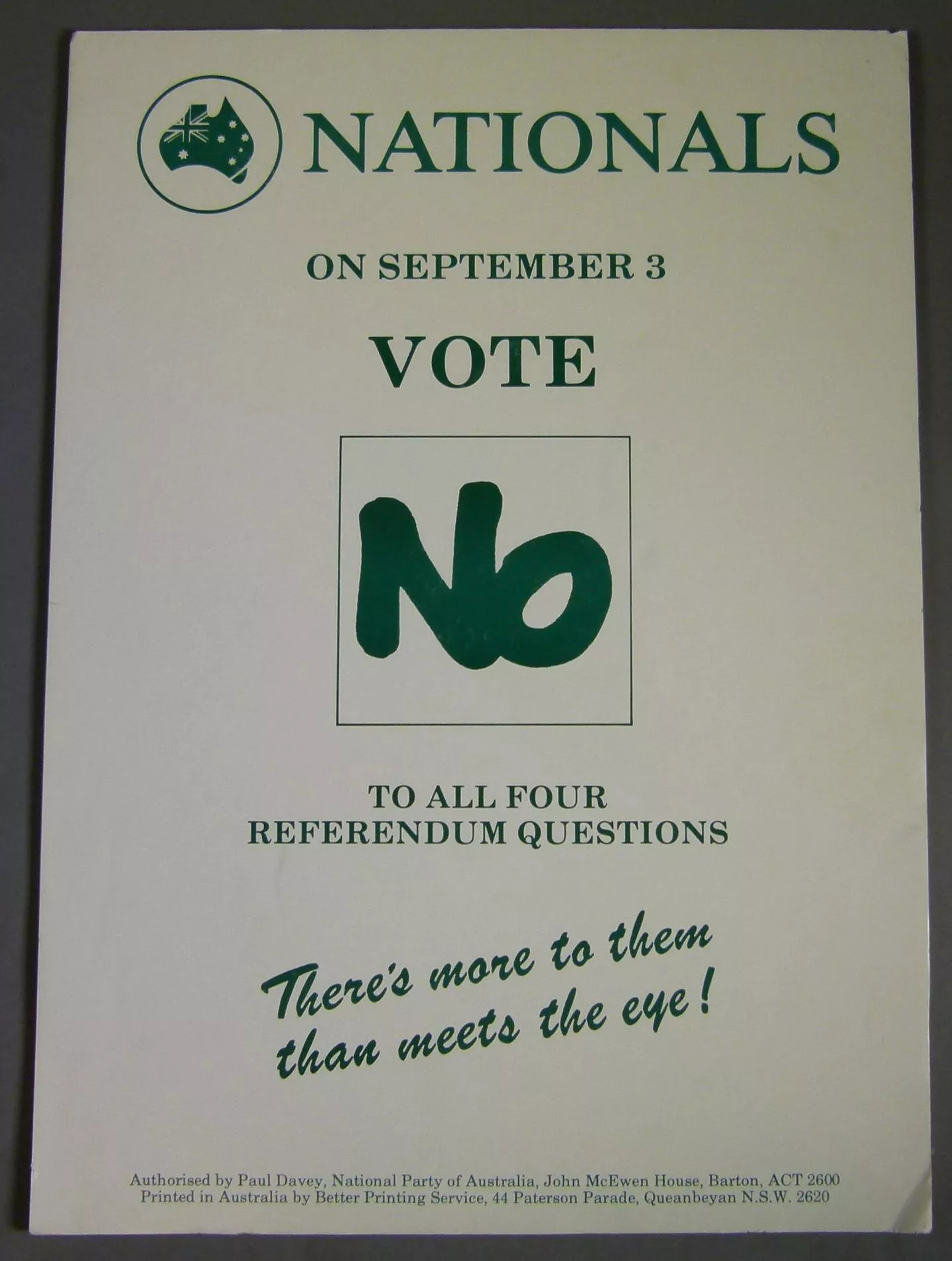

Booklet outlining the NO case, 1988. Both the Liberal and National parties adopted 'no' as their official position and distributed branded material, hoping to capitalise on the referendum's failure.

Museum of Australian Democracy Collection R18.106

Extract from the official NO case

'There is a common theme to this referendum – more power to the central government in Canberra.

Freedom of religion in Australia is not currently under threat. Why replace certainty with uncertainty?

Government funding to Church and other private schools is today secure. If this proposal is carried, there is no guarantee that such funding would continue.

The proposal is so ambiguous and flawed that other established religious rights could be directly threatened, among them prayers in schools and the broadcasting of religious programmes.

The trial by jury proposal is hopelessly flawed and would undermine our existing rights enshrined for seven centuries since Magna Carta. It paves the way for majority verdicts – perhaps two out of only three jurors – and for juries to be chosen on the basis of race, sex, education ... or other grounds.

Australians already have adequate safeguards in the important area of compensation for property compulsorily acquired by governments. It would allow the government to confiscate the property of a Territory government without the need to provide any compensation.

DON'T ENDANGER THE RIGHTS YOU ALREADY HAVE. VOTE "NO".'

Source: Official referendum handbook, MoAD item 12445

Did you know...?

This referendum delivered the highest national NO vote of any referendum held to date.