The history of misinformation and disinformation

False information from ancient times to the present.

False or misleading information is not new and has likely been present ever since information has been shared between people. Throughout history, we can find examples of the three most common types of false information: misinformation, disinformation and malinformation.

Misinformation is false and misleading information created or shared by mistake, without the intent to mislead.

Disinformation is false and misleading information created or shared to deliberately mislead people.

Malinformation is information based in fact that is manipulated, presented out of context, or shared to deliberately cause harm.

False and misleading information throughout history

'Fake news' in ancient Rome, first century BC

As far back as ancient Roman times in the first century BC, historians wrote about a propaganda war between Julius Caesar's heir, Octavian and his rival, Mark Antony. Both Octavian and Antony are said to have circulated propaganda on coins, poetry, pamphlets and in speeches to gain public and military support. However, Octavian cast a decisive strike when he read Antony's alleged will aloud in the Roman Senate. The will reportedly revealed Antony's allegiance to his lover, Cleopatra Queen of Egypt, rather than the Roman people – winning Octavian support from the Roman Senate and the people. Whether the will was Antony's or a fabrication – i.e. malinformation or disinformation – is disputed amongst historians, but either way it contributed to Octavian eventually becoming the sole ruler of Rome.

Plague disinformation, 17th century

Flash forward to Italy in the 1600s when health disinformation was present during the black plague. To avoid going into quarantine and the associated financial and social impacts, cities often misreported or misrepresented plague numbers. Spreading rumours of plague elsewhere was sometimes used for political advantage as well.

The Great Moon Hoax, 19th century

In 1835, New York's The Sun newspaper created the so-called 'Great Moon Hoax'. The newspaper printed claims of life on the moon, including men with bat wings, 'man-bats', as well as unicorns and other mythical creatures. The claims were reprinted in multiple papers and elevated The Sun, for a time, to one of the most widely read newspapers in America. The goal of the hoax may have been to increase sales and readership.

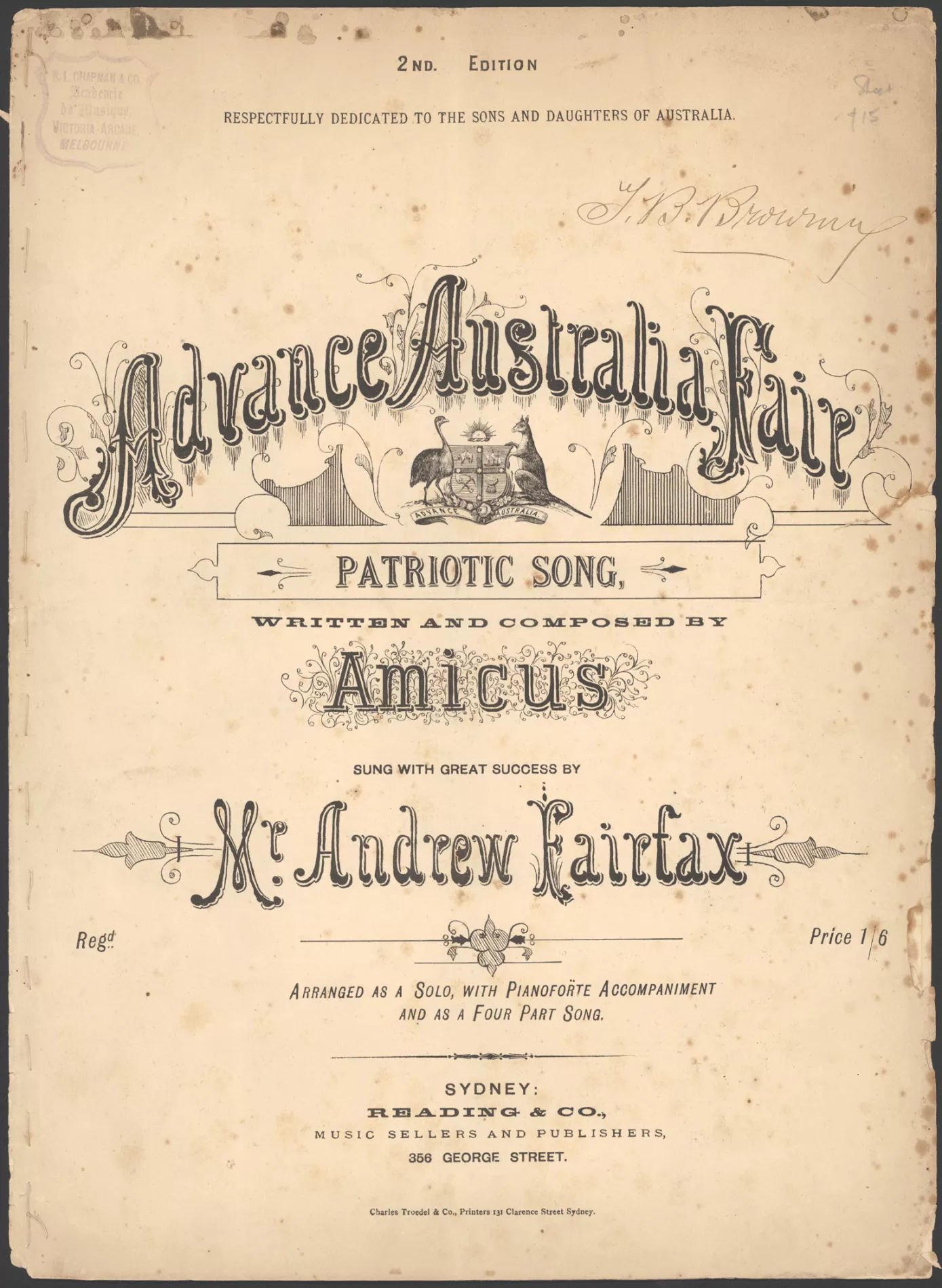

Australian wartime propaganda, 20th century

In Australia, propaganda was used during the First World War when the government held the 1916 and 1917 conscription plebiscites. A plebiscite is a national vote on a topic, sometimes called an 'advisory referendum' because the government does not have to act upon its decision.

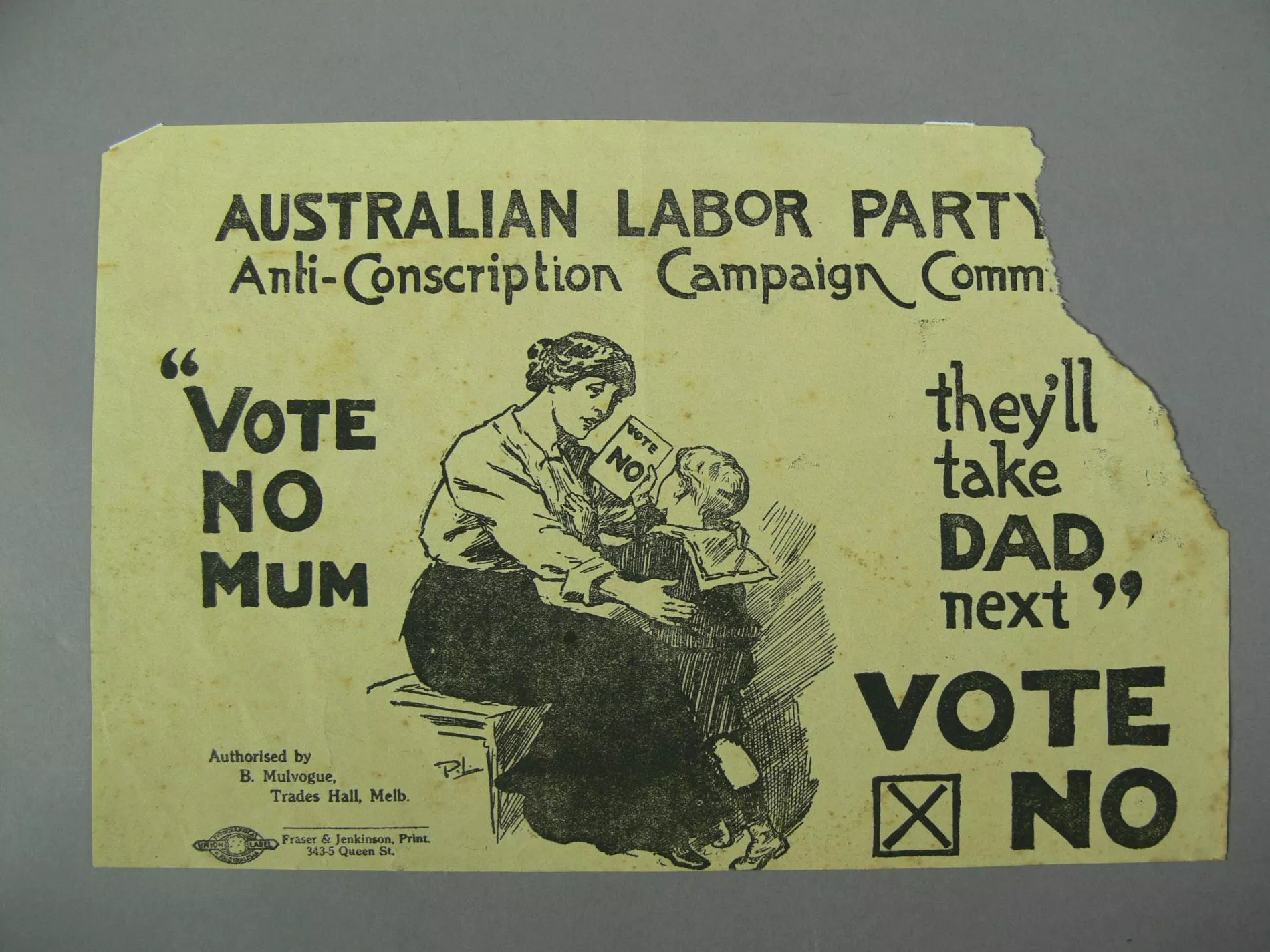

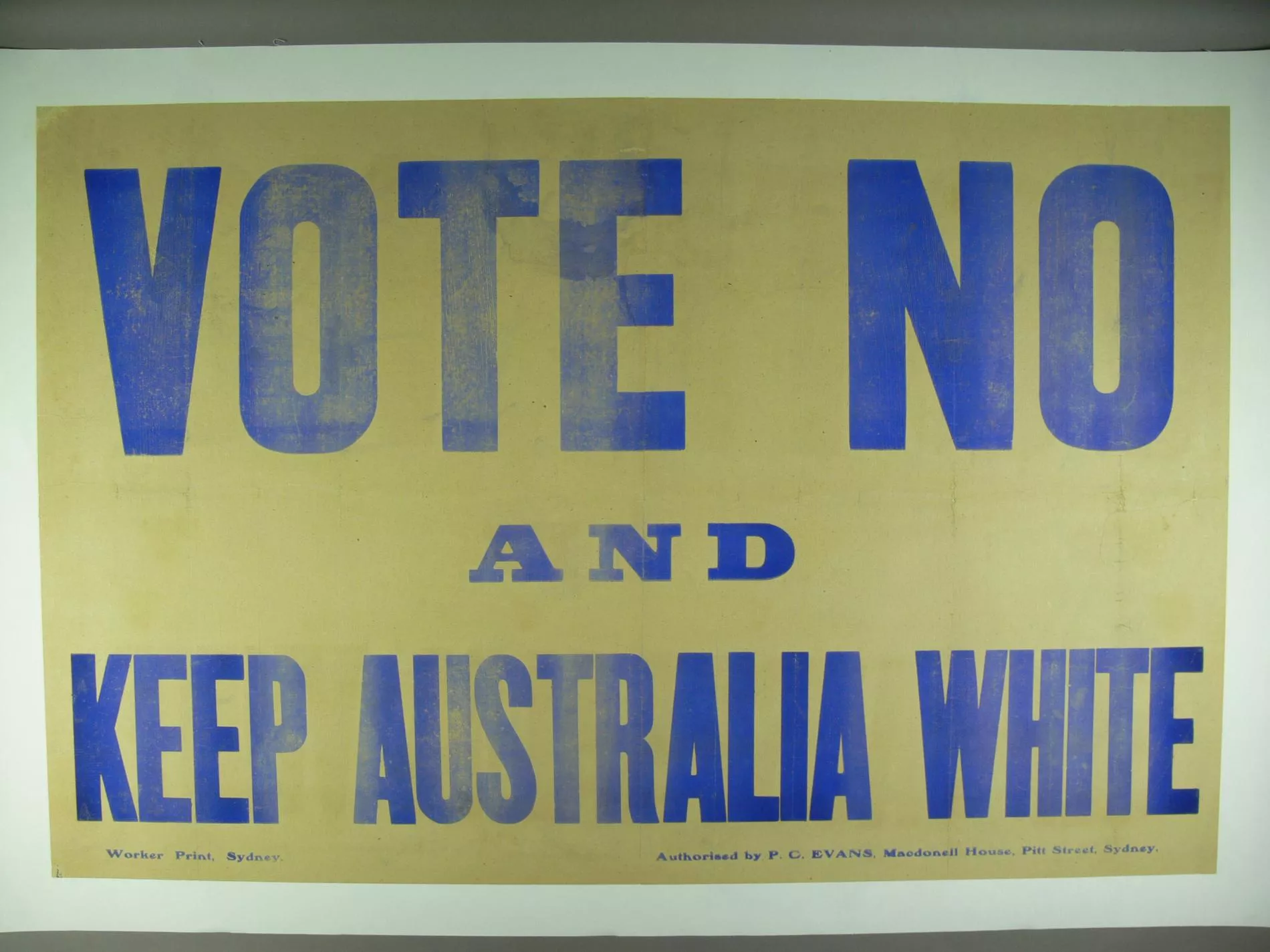

The conscription plebiscites asked Australians to vote on compulsory conscription (i.e. requiring men to enlist for service overseas). Political parties created posters encouraging 'yes' and 'no' votes, aiming to influence people by using emotion, fear, or patriotism. While some of the messages in these posters may have been based in fact, as they were presented in a particular way to take advantage of emotion and influence a political outcome, they are examples of propaganda.

Anti-conscription poster, 1917. Racial prejudice drove at least one of the arguments against conscription – the potential for it to reduce Australia's white population and force Asian or Pacific labourers to be imported. Museum of Australian Democracy collection 2014-0236

Anti-conscription leaflet from the 1917 referendum. Similar arguments for and against conscription were employed in both 1916 and 1917. Museum of Australian Democracy collection 2016-0103

JFK conspiracy theories, 20th century

Following the assassination of US President John F Kennedy (JFK) in 1963, conspiracy theories began to circulate blaming US agencies such as the CIA, other governments, or underworld organisations like the mafia for his assassination. Books, documentaries and websites were dedicated to JFK conspiracy theories.

Harold Holt goes missing, 20th century

In Australia, the accidental drowning of Prime Minister Harold Holt in 1967 on Cheviot Beach in Victoria was followed by the circulation of conspiracy theories, including that he had faked his own death and was still alive operating as a Chinese spy. These theories were fuelled in part because Holt's body was never recovered, leaving many people with lingering questions.

Chorizo in space, 21st century

In 2022, a French scientist shared a photo on social media of what he said was a star, taken by the James Webb Space Telescope. Shortly afterwards, he revealed the image was in fact a slice of chorizo. The scientist admitted the post was intended to amuse and to remind people to question images even if they are from credible sources. This is an example of well-intended disinformation.

Contemporary culture of misinformation and disinformation in Australia

The evolution of technology and how information is shared, from word of mouth, to print, radio, television, internet and social media, has increased the speed and ease of creating and spreading misinformation.

During recent election campaigns, concerns that 'deepfakes' – videos of people that have been digitally altered to spread false information – were used to sway people's votes against them. Online financial scams featuring fake celebrity endorsements, conspiracy theory movements originating overseas and spreading online, and more digital schemes can all be found in Australian online media.

Throughout history, misinformation, disinformation and malinformation have played a destructive role by aiming to manipulate people's beliefs and understandings about their communities and countries. Today, digital and social media have allowed misinformation to be more prominent than ever and it is important to be aware of its impacts on us and the people around us.

What is propaganda?

Propaganda is political information, opinions, arguments, ideas and images that are spread or broadcast with the intention of manipulating and influencing public opinion. Propaganda is not always false, but is always designed to support a particular argument, and can be misleading.

What is a hoax?

Information that is created to trick people into believing things that aren't true or real. A common hoax you might see on social media is a false claim that a celebrity has died.

What is a conspiracy theory?

An explanation of an event that rejects the accepted or official account. Often a conspiracy theory will claim the event occurred due to behind-the-scenes manipulation or a plot by a small, powerful group.