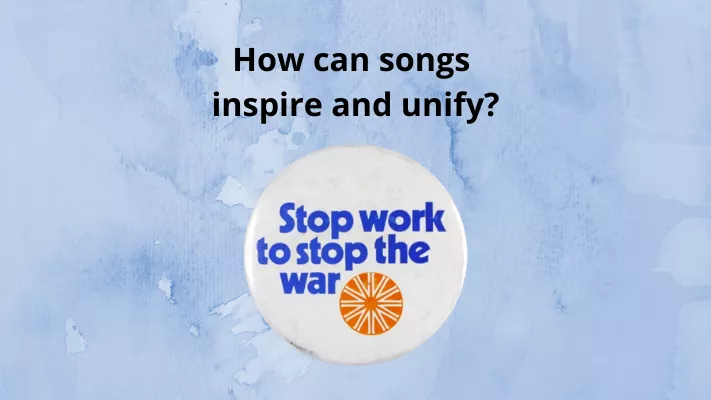

Protest music

Explore the power and role of music in the history of protest.

This podcast explores the role of music in the Vietnam moratorium protests in 1970. Explore the power and role of music in the history of protest. How can songs inspire and unify and help us express shared feelings and freedoms?

Protest music and the Vietnam Moratorium

0:00

Person 1: This is a MoAD Learning podcast. Today, Neil is going to be discussing protest music and the Vietnam Moratorium.

Neil: Today, we're looking at how music can be a part of using our voices to have our say; how we can use music to talk about issues we're passionate about; how music can be used to exercise our freedom of speech. To do all this, we're going to look at protest music and four songs as examples. As we look at them, we'd like you to think about what the music you listen to expresses. A reminder, that to accompany this podcast, we've also created a Spotify playlist with a selection of songs to listen to, as well as an activity sheet. So, after this podcast, you can analyse the songs and consider how and why they were important to their audience. You might also like to do some research into the social history behind the songs. Okay, let's go.

We see political protests in the news, and it's not that unusual. Political protest has a long tradition as a way of expressing disagreement or asserting rights and freedoms. Black Lives Matter, climate change, these are important issues that people feel strongly enough about to gather together and challenge for change on the streets. But there was a time in Australia when having your say through gathering together and protesting in public wasn't well accepted. Protests about rights and freedoms was seen by the authorities as a threat to the stability of the social order. We're going to look at an issue that helped change this perception, an issue driven from the grassroots of individuals – an issue where music was a unifying expression of how people were feeling. An issue where protest could also be a song.

In the 1960s, Australia was involved in a war in Vietnam. While this initially had popular support, increasingly, people felt this was wrong, and wanted to oppose it; even gathering on the streets and protest. In 1970, there was a national day of street protests across Australia called 'The Moratorium'. Moratorium means the stopping of an activity for an agreed amount of time. By using this word, the protest organisers hoped to stop Australia's involvement in the war. The Moratorium brought together many different groups opposed to Australian involvement in the war. Interestingly, school and university students joined in the marches in large numbers. Why would they do that? At the time, there was actually a lot of discussion about whether they should have a voice and use their freedom of speech to support this cause. Do you think they should've left school to protest? And how do you think their participation could've helped the cause? Perhaps, put yourself in the shoes of those students who wanted to attend. Think about how they might've been feeling at the time.

The protesters were inspired by Moratorium marches in the United States, where American involvement in Vietnam was highly controversial. They were also inspired by protest music they'd heard, or seen, on TV.

Let's think about how music can bring people together. Music can say things that are hard to express. It can fill a void in the media about issues; it can be another voice. And it can help people connect and unite. In the days before the internet, music was a bridge to other people. For many people, music was the internet. Take a moment to think about how you connect with other people about your passions.

Let's take a look at some music at the time that expressed people's feelings and their political ideas, starting with a song Moratorium marchers in Australia sang together as they marched. The song is called Give Peace a Chance, and it was written by John Lennon. This was the first solo song released by a member of one of the most famous bands in the 1960s, The Beatles. It was a song that expressed the confusion which many people felt about the arguments around the war. John Lennon was already famous, and on this issue, he was the Greta Thunberg of his day, only bigger. When the marchers sang this song, they felt like they were joining with people across the world; joining with one of their cultural heroes, and democratically expressing their views.

Let's hear from someone who shared in that protest.

Bernie Howitt: In May 1970, I was in year 11 at Kogarah High School, and bitterly opposed to the war. I was still too young to be conscripted, but that fear was always there. I came from a family of a trade unionist father, and he was also opposed to the war, he'd fought in World War 2, and said he fought that so I didn't have to fight. And, when the opportunity came to participate in the Moratorium, they supported me fully. I left school in the middle of the morning to catch the train into Sydney, to walk up to Sydney University to thousands of people assembling to march down through the streets of Sydney, and the first time I felt that I belonged to a group of people. We were united to try and change something and do something that we felt was wrong.

So, with 20 to 30,000 people walking down George Street, the main street of Sydney, it was amazing feeling of community, and when we started chanting Give Peace a Chance, that song resonated so strongly for all of us, and you really felt you were connecting. In those days, before internet and instant communication, music was what kept us together, and it enabled us to feel that just by simply singing a song, walking down George Street, we were communicating to the other people in Australia that we felt things had to change, certainly to our government that we should no longer be in Vietnam, and providing solidarity with peace movements around the world that were springing up. And knowing that someone in Stockholm or San Francisco could be singing Give Peace a Chance and be part of that very same movement.

Neil: That was Bernie Howitt, who was a 16-year-old student at Kogarah High School in 1970. The Moratorium marches were so large, and so well organised, and brought together so many different groups. From mothers concerned about their sons being forced to fight, to teachers, shopworkers, people from so many walks of life, including students, that peaceful protest became more acceptable to the wider community. It looked like the community on the street coming together to support a cause.

Sometimes, soldiers in Vietnam also used songs as protest. They listened to and played the same protest music as the people at home – sometimes they wrote and played their own songs about their experiences, which may also have been protesting about being involved in the war, or protesting about the way the war was being conducted. One song that resonated with everyone was We Gotta Get Out Of This Place. This song was recorded in 1965 by an English band about two lovers running away to seek a better life, away from a dirty industrial city. It became very popular at high school graduations – maybe you can imagine. This song was not written with protest in mind, but as the war progressed, the lyrics assumed another meaning for the soldiers in Vietnam and the protestors. It came to mean 'we gotta get out of Vietnam'. And people from both sides of the issue could agree with the feeling of the song.

Let's look at a song called War, written around the time of the Moratorium march in Australia. War is a song against all war, but its writing was inspired by the war in Vietnam. It was released by a commercially successful group, but re-recorded by another artist, as the recording company thought the anti-war lyrics would hurt sales for the first group, so it was sung by lesser-known artist Edwin Starr, who turned up the passion of the song. It seems the best protest music is more about feelings than politics. What do you think about that? Can you think of any music you listen to that uses feelings or empathy to engage you in an issue? Do you agree feelings are a useful tool in music to help engage listeners and help bring them together?

Now, let's jump forward a little, past the Vietnam War, to a different kind of protest, with music. In 1988, famous American musician Bruce Springsteen was invited to perform in a free concert in East Berlin. Bruce Springsteen had a huge hit with the song Born in the U.S.A. which was actually a song about Vietnam veterans, but the song had become an anthem about rights and freedoms. At the time, Berlin had been separated into halves at the height of the Cold War, by a wall, to stop people from seeking the freedom of democratic West Berlin. Hundreds of thousands of people heard Bruce Springsteen and his band sing about another, more democratic way of life – it showed them there were alternatives, and it inspired people to think about change. The wall was torn down the next year.

Now, we have some questions for you:

- How would you like the world to be? Is there anything you are passionate about that you want others to know about? How are you sharing your ideas, because you have freedom of speech?

- Are you a musician? Could you use music to educate listeners about particular issues?

- Could you be an active citizen who helps to create support and momentum for an issue which could lead to lasting change?

Be it rock, folk, hip-hop or whatever, use your style to create music that speaks to the issues you are passionate about. You have a voice, so feel free to use it.

If you want to listen to even more, we've created a range of protest playlists on our website – search for '33 Revolutions' at moadoph.gov.au.

After all, people have the power.

Person 1: This was a MoAD Learning podcast. Don’t forget to check out playlists, worksheets and more at moadoph.gov.au/learning.