First Nations readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people.

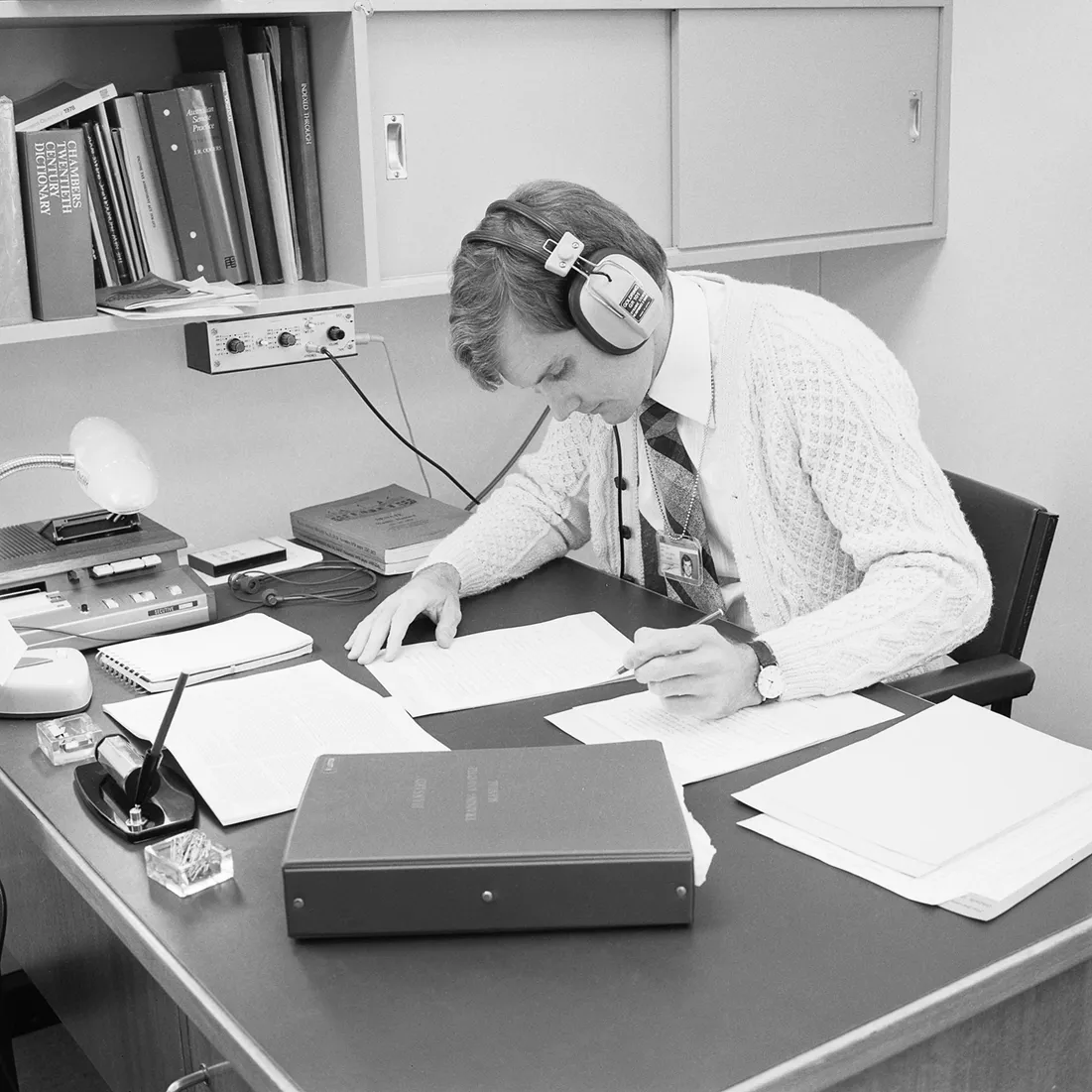

Following weeks of active protest activity, this could have prompted an immediate and urgent police response, or at least a stern eye from security staff. But today, those who exited the van had come to restore.

From the van, the conservation team emerge. They carry specialist tools, black protective gloves and rolls of foam wrap. They carry their equipment through the main museum to the front doors, past empty rooms and silent exhibitions. They set down their gear and take in the job before them.

More than a century ago, a jarrah tree stood tall in the forests of south-west Western Australia. Along with its brothers, it was felled, transported, and cut into boards. These boards then lay in a timberyard, waiting. Soon enough, they were selected and shipped to a Sydney workshop. They were measured, cut, and stacked in four layers. Windows were installed, then brass handles and push panels were added. Decorative beading was fitted around the perimeter. They were sealed, varnished and polished to gleaming red-brown before being transported to Canberra. There, for decades to come, they would serve proudly as the front doors to Australia’s Parliament.

The centrepiece of Parliament House

The front doors of Old Parliament House were designed in 1924 by Commonwealth Chief Architect, John Smith Murdoch.

Western Australian jarrah was chosen for the doors due to its weather resistance. Even in the 1920s, Canberra was known as a city of extremes, with icy winters and scorching summers requiring buildings that could endure all conditions.

Jarrah’s density makes it naturally fire-resistant. Though Mr Murdoch didn’t know it at the time, his choice of wood would later help protect the building from being engulfed by flames some 95 years later.

The doors were originally manufactured and installed by H & E Sidgreaves Ltd, a family business operating out of a busy studio in Redfern, Sydney.

Brand new and shining red-brown in 1927, the front doors stood proudly as the Duke and Duchess of York officially opened the Provisional Parliament House.